Milton A. Eisenberg

U.S. Army, 14th Evacuation Hospital

China-Burma-India Theater

14th Evacuation Hospital

During World War II, Milton A. Eisenberg was a master sergeant with the 14th Evacuation Hospital in the China- Burma-India Theater. The theater was at the end of the supply line and last on the list of priorities and supplies. He shared his recollections when he spoke at the World War II Lecture Institute in Abington, Pennsylvania July 15, 2003. Many of his remarks are historic, others are nostalgic and some are downright humorous.

You're in the Army Now

I came close to winning a lottery in 1940. During the Selective Service Draft, my number was the tenth one picked from a drawing of more than 1,000 others. At the age of 21, I was "caught in the draft" and expected to serve in the military for one year. That was before Pearl Harbor. Almost five years later, I returned to civilian life.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent his greetings and ordered me to report to my local draft board March 1, 1941. After delivering a canned speech, the board chairman handed me a token good for a bus and train ride to the induction station at the Philadelphia Armory. I joined a room full of draftees struggling through physical and written exams. A sergeant was impatient with the slow answers he received from the fellow ahead of me in line. When my turn came, I rapidly gave my name and address. Glaring at me, the sarge barked, "Oh, we have a fast talker here."

Following a battery of tests, I was inducted into the army and given a railroad ticket to Fort Meade, Maryland. Upon arriving that night, my first army dinner was cold, overcooked meat, sauerkraut and black coffee. A sergeant assigned me to a barracks in time for "lights out". When I received a G.I uniform, the shirt sleeves were too long, My flannel trousers were leftovers from the Civilian Conservation Corps. The leggings dated from the first World War. At least my hat fit.

The dreaded bugle sounded at 5:30 every morning. Like other rookies earning $21 a month, I exercised, policed the grounds for cigarette butts, drilled, marched, peeled potatoes, walked guard duty and tended to furnaces. After receiving typhoid and small pox "shots", I developed a fever and spent the night in a hospital.

While on K.P. duty, the mess sergeant handed me a scrubbing brush and bar of soap. He ordered me to clean a half dozen huge aluminum pots. As I vigorously scrubbed a container of brown, syrupy liquid he bellowed,"What in hell are you doing?" The soap was swimming around in the foamy chocolate pudding he later served at dinner. I skipped dessert that night.

Two weeks later, I was on my way to the Medical Training Center at Camp Lee, Virginia. We drilled on the historical Petersburg battlefield, the scene of a Civil War battle in 1865. My classes included medical subjects, army regulations, record keeping and sanitation. I learned how to use a gas mask and walk for miles with a full field pack and aching feet.

Draftees were just learning how to cook and I realized why an army dining room was called a "mess hall". One evening, when our dinner turned out to be a watery soup with tasteless dumplings, the soldiers finally rebelled. They banged on tables and demanded decent food. After that episode, our meals improved slightly.

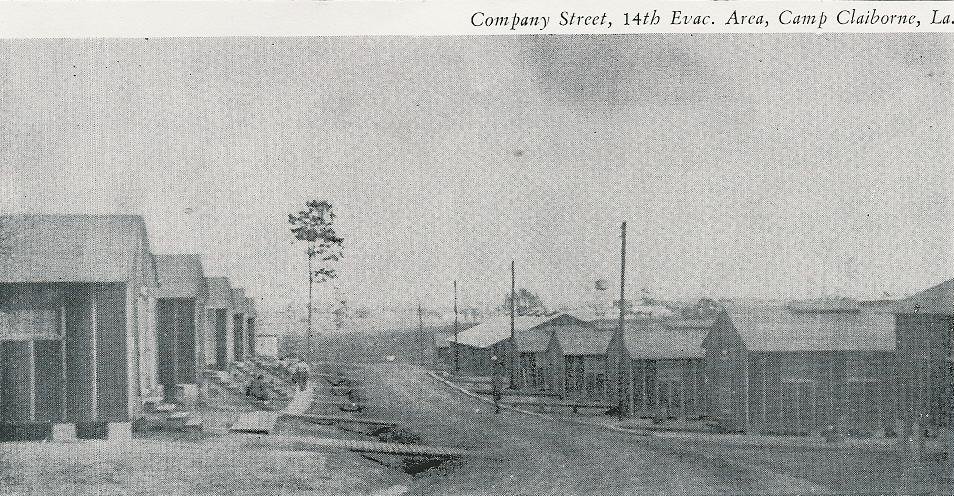

After three months, I completed basic training and joined the newly created 43rd Evacuation Hospital at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana. Two medical officers and 150 enlisted men comprised the unit's complement. Classified a personnel clerk, I handled the payroll, records and correspondence although there were no manuals or written instructions. When the army established service schools, I attended administration and classification classes. After serving as a corporal, I was promoted to staff sergeant.

Once I failed to follow the old army rule, "never volunteer". While our unit drilled, a medical officer asked if anyone could take notes and type. That sounded better than marching in the hot sun, and my hand went up. We drove into town and arrived at a funeral parlor. The officer then performed an autopsy on a soldier killed in a car crash, while I took notes. On the ride back to camp, I carried jars containing the vital organs. I skipped several meals after that.

On Maneuvers

During the 1941 Louisiana maneuvers, we functioned as an evacuation hospital. We pitched tents in a muddy school yard in hot and humid Lake Charles. Headquarters assigned us to General Krueger's "Blue"Third Army. Our forces "invaded the enemy" and Lieutenant General Ben Lear and his "Red" Army "defended" against the attack. Of course, our side won. Much credit went to a Colonel Dwight Eisenhower, who received recognition in later years. When maneuvers ended, we returned to Camp Claiborne, Besides Caucasians, our unit consisted of Filipinos, Mexicans, Native Americans, Cubans, Syrians, Guatemalans and Puerto Ricans. There were no African Americans in our unit. In later years, the military service was integrated.

The army adopted an eighteen-month extension of military service August 18, 1941. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, they extended my military service for the duration of the war. New personnel poured into our unit from all over the country. Our strength rose to sixty medical and administrative officers, fifty nurses and 300 enlisted men. Civilian occupations for the drafted enlisted men included coal miner, caddie, stableman, lawyer, parachute packer, optometrist, funeral director, bank teller, clerk, radio-script writer, brick layer, student, teacher, and others. In the army, they became medical technicians, cooks and supply clerks.

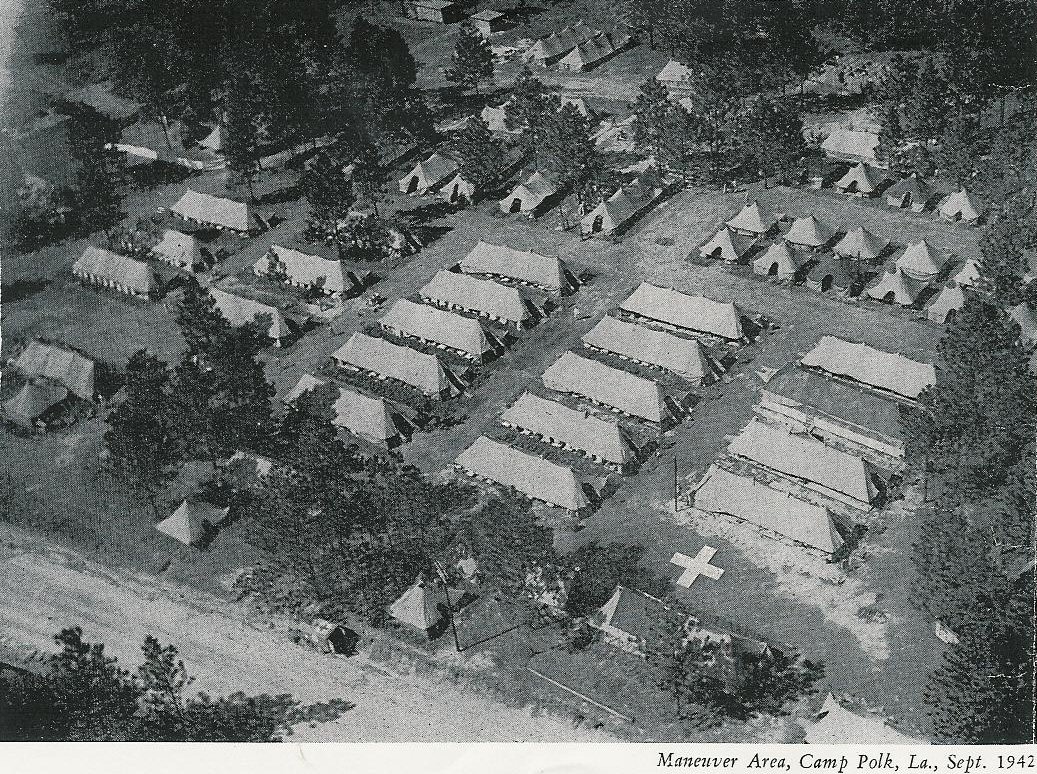

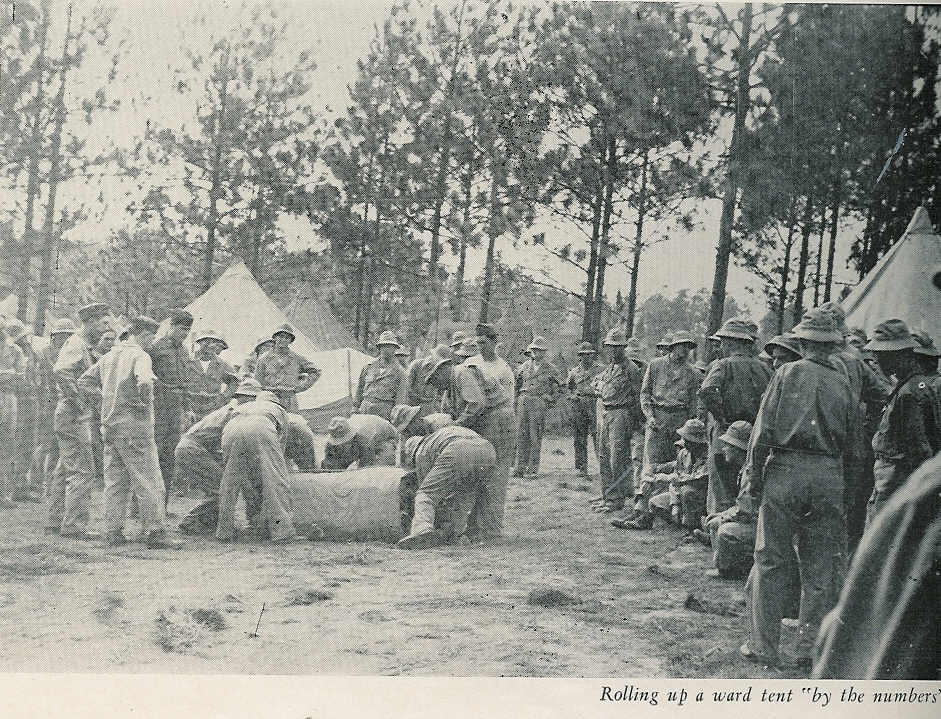

We took part in Third Army maneuvers at Camp Polk, Louisiana starting July 1942. Our group shifted from strangers to a unified team that played a vital role in the maneuvers. We pitched hospital and living quarter tents. Male officers lived on Brass Hat Row, while nurses made their homes on Maiden Lane. Enlisted men lived on Tobacco Road, and the latrine was on Canal Street. When Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, inspected our unit, he questioned me about the personnel section. I sweated until our commanding officer assured me that the general was pleased with our meeting. A former enlisted man, the general declined an invitation to visit the officers' club stating he preferred to inspect the enlisted men's latrines and mess.

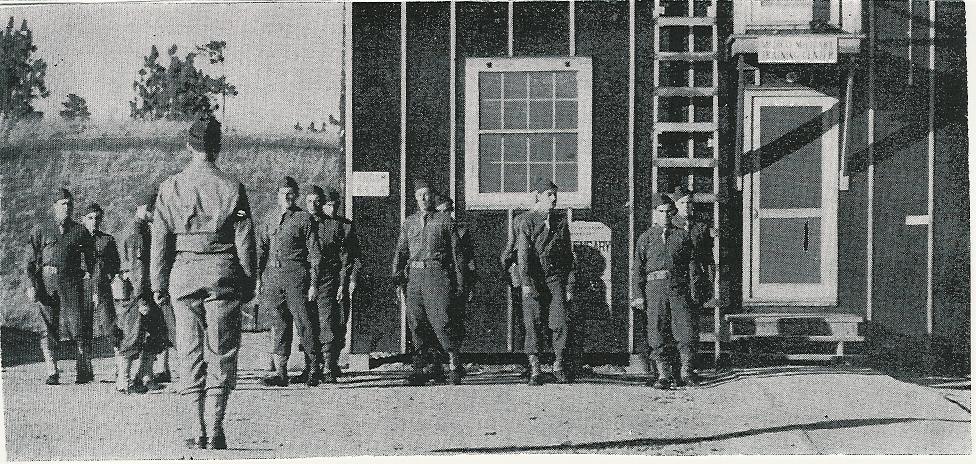

Our unit was redesignated the 14th Evacuation Hospital August 15, 1942. Colonel Leonard Swanson, a regular army medical officer assumed command, and we returned to Camp Claiborne. Rookie medical officers, nurses and newly drafted soldiers took part in an intensive training programs. Now, a technical sergeant, I taught classes in army administration and military correspondence. We endured practice alerts and exhausting inspections. There were long hikes and overnight bivouacs. Everyone had to walk through a tear gas chamber and undergo a belly crawl with live ammunition overhead.

Aboard USS West Point

Flowing several false alarms, the big day came. On June 17, 1943, we packed our equipment, boarded trucks and headed to the railroad station. Our destination turned out to be Camp Shanks, New York. The camp swarmed with soldiers preparing for overseas duty. My personnel section processed voluminous records and issued "dog" tags. Everyone received a full quota of clothing, haversacks, pistol belts, canteens, and shelter tents. The lucky ones, who lived nearby, received weekend passes. Others went sightseeing in New York. I was one of the lucky ones.

Accompanied by a military band, our group boarded the troop ship, USS West Point (built the SS America) at Staten Island, New York, July 9, 1943. No one knew where we were headed, and the rumor mill was busy. Aboard the ship, we slept on canvas hammocks, slung three high from iron pipes. Each day, we took part in "abandon ship" drills. Because of overcrowding, we waited in line for two meals a day. Breakfast consisted of stew and black coffee. For dinner, we usually had beans, stew, and coffee. We ate on deck, wore life preservers with an eye on the Radar. I celebrated my 24th birthday with a treasured Hershey Bar.

When the ship crossed the Equator, everyone aboard took part in a traditional naval ceremony. Those crossing the Equator for the first time were called Pollywogs. They became Shellbacks and received certificates commemorating the event. The ship stopped for provisions in Rio de Janeiro where nobody was permitted to go ashore. The next stop was at Capetown, South Africa, where commissioned officers left the ship, to the chagrin of the enlisted men. Colonel Swanson finally revealed we were assigned to the China, Burma, India Theater. We had orders to construct and function as an evacuation hospital in Assam, India and operate medical aid stations in Burma.

Welcome to India

After zigging and zagging, the ship finally docked at Bombay, India. Following thirty-five days at sea, I was eleven pounds lighter. Although we were anchored far from shore, there was a strong stench of sewage. We disembarked August 14 and traveled by lorry to a British Rest Camp at Deolali. We relaxed as we learned about local currency, Indian customs, and how to haggle with merchants. Most of the Indian people who opposed the war were friendly to American soldiers.

Beggars, including small children, lined the crowded, filthy streets, and cows had the right of way. I bought a beautiful leather brief case at the bazaar. A few weeks later, the unprocessed leather smelled like a dead animal, and I threw it away. As I purchased souvenirs, a merchant told me he collected American coins and asked if I had any. I handed him a few quarters. He thanked me profusely. As I left his store, I saw a sign in his window reading "Foreign coins exchanged."

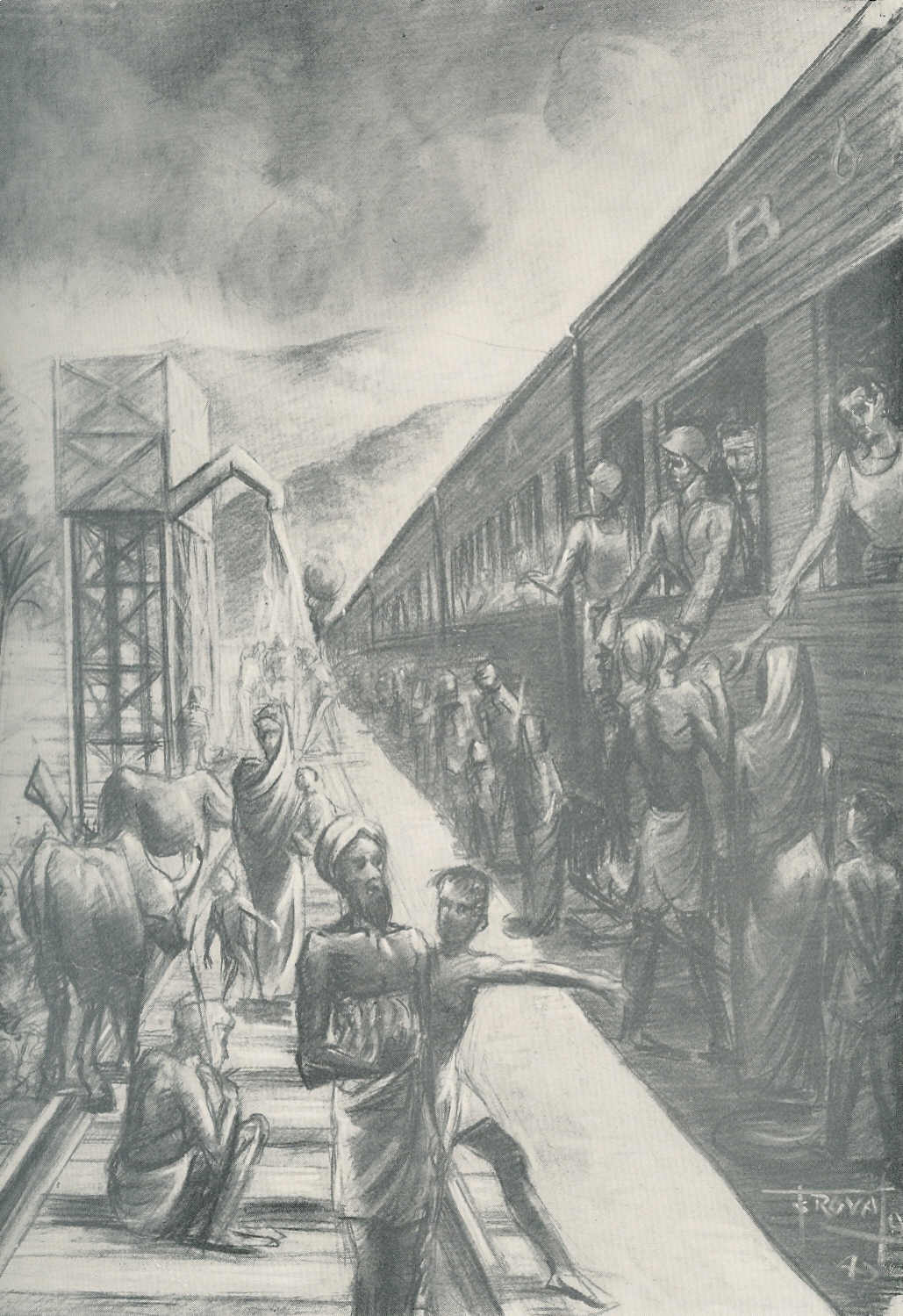

We boarded a narrow gauge rail train in Bombay, August 20. This began a 1,500 mile trip to the Assam jungles. We slept on wooden benches and shared a drinking fountain for bathing. British and Indian rations ranged from bad to mediocre. When we learned that the British mess sergeant hoarded our American food, he was forcibly removed from the train. (Don't ask how.) For the remainder of the trip, we enjoyed our meals.

In Dhubri, we set sail on "The Buzzard" an old river boat. We sailed up the Bramaputra river for two days. At Pandu, the group boarded railroad coaches. We then traveled through jungles, tea gardens and small towns. After 36 hours, we reached Margherita, near the Burma border in northeastern Assam. We remained for several weeks, housed in bamboo bashes. It was eleven days since we left Bombay. During the monsoon season, the rain accumulates fourteen inches in twenty-four hours. (The Army did not issue umbrellas as standard equipment.)

14th Evacuation Hospital - Open for Business

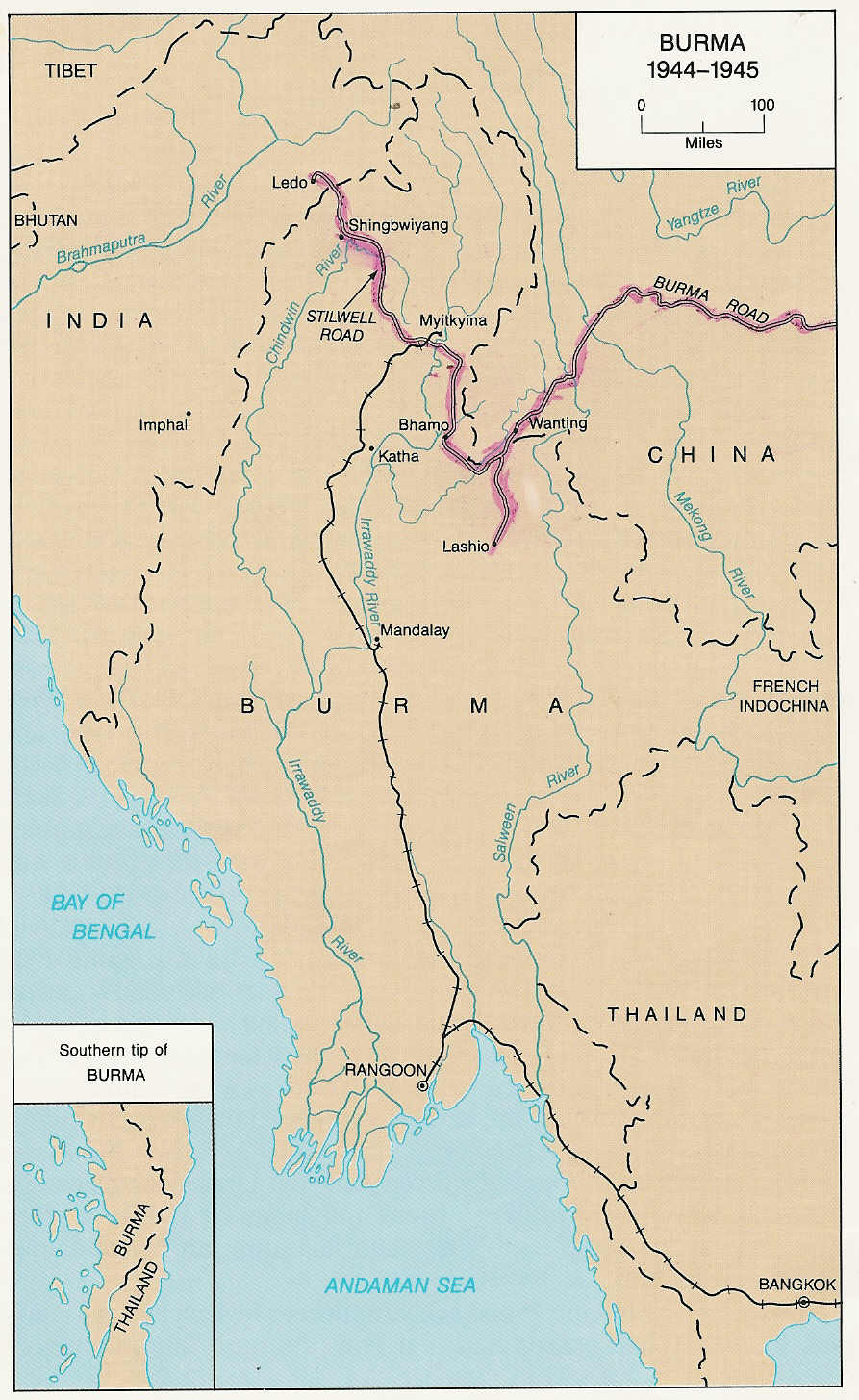

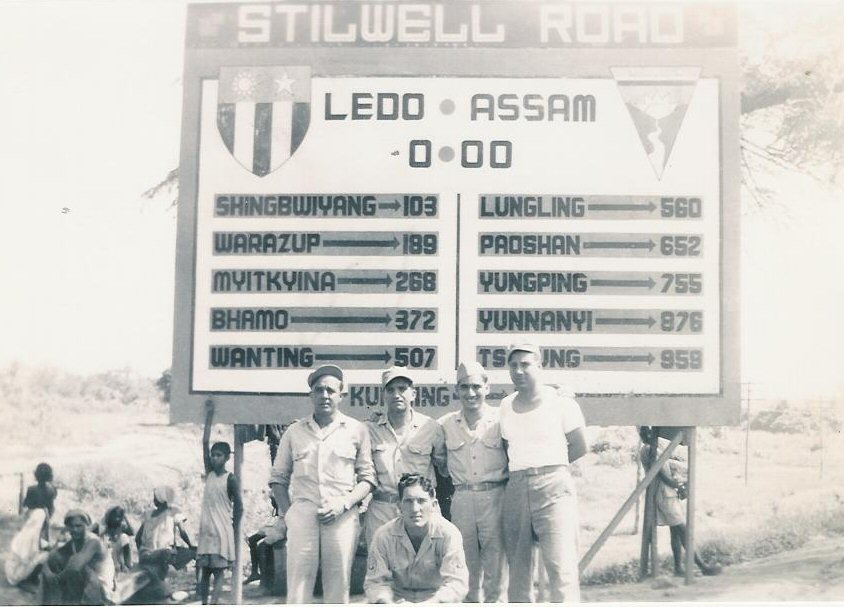

Our unit arrived in Ledo, Assam, India September 11 and traveled 19 miles on the newly built portion of the Ledo Road. Japanese troops had captured the Burma Road and controlled the seaports and railroads cutting off supplies to the allies. Supplies came from the United States by ship to India, then by rail to Assam. They were then airlifted over the Hump, the world's highest mountains. American engineers, working with Indians, Chinese and Burmese were building a road that would connect Ledo, Assam with the Burma Road. This would open a land route for the flow of supplies to the allies fighting the Japanese army. Bulldozers and steam rollers transported across two oceans were used in the construction. Our hospital was to provide medical care for American troops and allies.

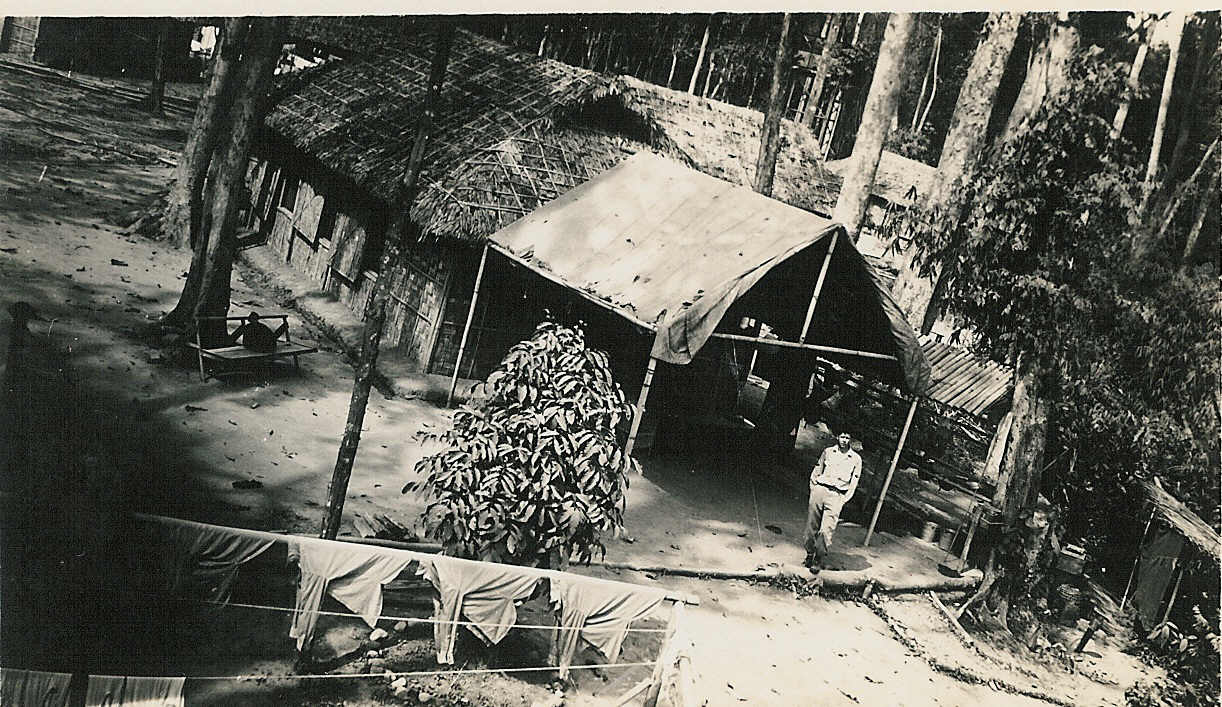

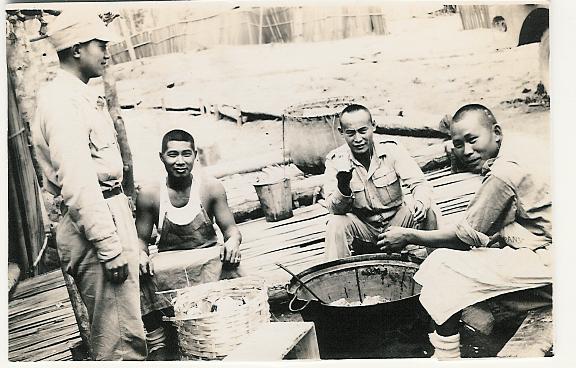

In the midst of the hot monsoon season, our men split into groups, each with a definite job to do. Some cleared underbrush. Others, working with American army engineers, built roads and dug ditches. The sanitary group triumphantly announced that a shower bath was working. It consisted of an open pipe leading into a large perforated tin can. An Indian military labor detachment arrived to handle sanitation and drainage details. These sharply dressed soldiers clicked their heels, stood at attention and saluted all day. They looked good but never did any work.

Working with Indian civilian laborers, our personnel built a bamboo hospital and living quarters in the jungle surrounded by bamboo trees and dense foliage. The hospital consisted of wards, operating rooms, clinics, and labs. For more than two years, I lived with nine others in a bamboo basha, with dirt floors, bamboo siding and a palm-thatched roof. Our address was Number 10, Downing Street. Monkeys amused themselves by jumping up and down on the roof. We finally became accustomed to the all-night jungle sounds. If air raid signals sounded, we headed for the slit trenches.

Our hospital opened October 10, 1943. The medical officers specialized in surgery, internal medicine, eye, ear, nose and throat, urology, psychiatry, tropical medicine, dentistry, pathology, pharmacy and radiology. Through them, younger physicians learned new techniques. Skilled nurses came from all parts of the United States. Enlisted men attended x-ray, laboratory, medical technician, cooking and clerical army schools.

A week later, we opened aid stations in the Burma Jungles of Nawn Yang, Taguang, Negaland, Changrang and Namgo, At Khalak Ga, we operated a fifty-bed hospital. Medics treated wounded Chinese soldiers, men from a brigade of British General Wingate's Chindits and local Naga and Kachin natives. These stations received supplies through air drops.

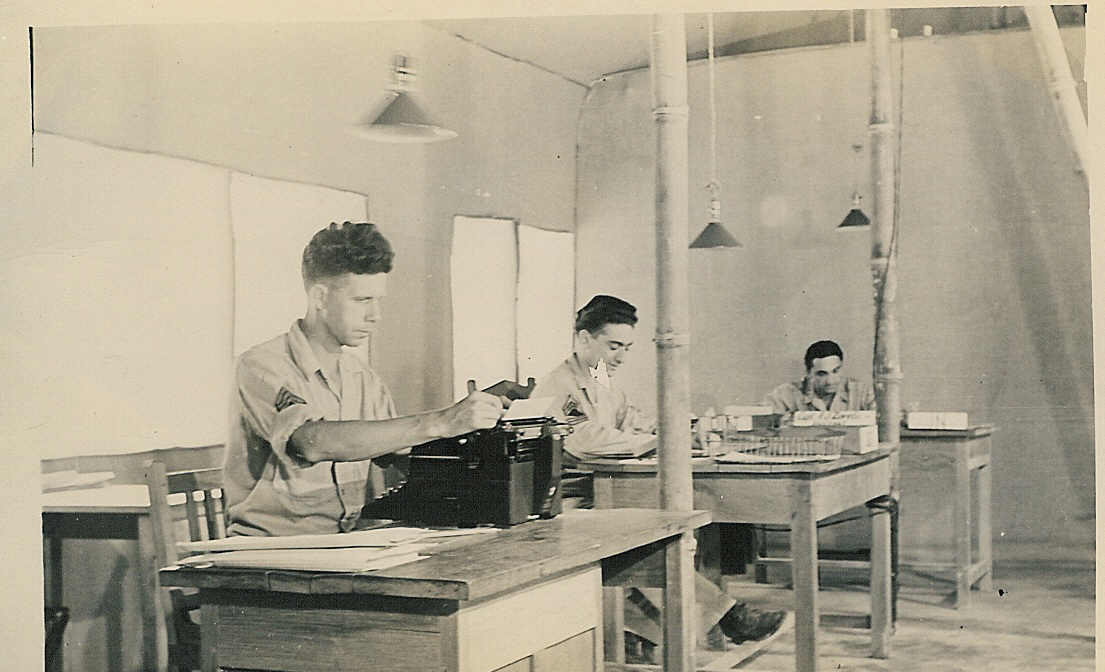

As a Master Sergeant, heading the personnel section, I worked with a well-trained staff. We handled official correspondence, payrolls, insurance, service records, and various administrative matters. When Congress authorized the naturalization of aliens in the armed forces, forty-five men applied for citizenship. They came from Spain, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Turkey, Switzerland, Holland and Lebanon. Some changed their names. Norman Zatz became Boris Norman, and Wilhelm Heinman picked William Heiman. The name changes messed up our records, but we eventually straightened them out.

Al Ziegler, a pleasant, pipe smoking New Jersey national guardsman, was first sergeant of our detachment. Respected by the enlisted men, he was twice the age of some of them. When, he returned home to his wife and daughter under the point system, Pat Burke, a popular tobacco chewing draftee from the Pennsylvania coal mine regions succeeded him.

Those were the days before computers, lap tops, copy machines, staplers, ball point pens and calculators. We used typewriters, mimeograph machines and adding machines. The story goes that a unit, with limited storage space, requested permission from headquarters to destroy obsolete files. Headquarters replied, "Permission granted, provided seven copies are made of each file destroyed."

Visiting U.S.O. entertainers included Paulette Goddard, Joe E. Brown, Jinx Falkenburg, Captain Melvin Douglas and Pat Brian. Pat and our chaplain disappeared into Father Fleming's quarters with a bottle or two. In the evening, Pat fell into a slit trench. Lord Louis Mountbatten, a handsome Britisher, created a stir among the nurses when he visited the hospital.

Our detachment commander, complying with army regulations, read the Articles of War to the troops every six months. He warned that contracting a venereal disease was a punishable offense. "If you do it and get diseased," he said, "I'll court martial you." A medical officer said, "If you do it and get diseased, I'll cure you." The chaplain said, "Don't do it."

Jungle Life

"The Bucksheet", a troop publication for the troops, said, "Assam is the brightest kaleidoscope in all these wars if you want to do a travelogue. If you want color, take Assam. But don't take it brother, skip Assam. You'll find local color fades in two days. The heat kills the color and the rain washes it out. And you'll never get a date - unless you're a better man than forty-nine out of fifty. No, don't go to Assam. Just read about it. Stay in Calcutta where you can get a gin and a lime and a date to go dancing at Firpo's where they don't serve rations. Stick to Calcutta."

Since we were located at the end of the supply line, American food was confiscated along the way. We were stuck with British food. Breakfasts consisted of powdered eggs and milk, soy bean sausage, canned bacon and coffee (?). For lunch and dinner, we had fatty corned beef, canned frankfurters, beans, chili and stew and mutton. "Fresh" water buffalo looked and tasted like shoe leather. No matter how Spam was prepared, it always tasted like Spam. When all else failed, we settled for creamed beef, also known as S.O.S. The standard noonday drink was a lemon flavored beverage commonly called battery acid. In those days, nobody knew or cared about low fat, low cholesterol and low salt diets.

We had to swallow salt tablets several times a day. This probably contributed to my high blood pressure. We took Atabrine tablets to prevent malaria, slept under mosquito netting and applied mosquito repellent. Despite these precautions, many in our unit contacted malaria and still suffer from it today. The sanitary unit added chemicals that gave the boiled water a strong iodine taste. Perrier was not available. To reach the six-hole latrines in the dark, we had to move fast and hopscotch over slit trenches. The Red Cross issued cards identifying us as medical noncombatants. There was a catch. The Japanese could not read English

Hindu and Mohammedan civilian workers lived in separate areas. My personnel clerk asked a young worker if he were a Hindu, The boy replied, "Nay sahib." When asked if he were a Mohammedan, again the reply was "Nay sahib." Finally, the clerk asked "What are you?" He proudly said, "I am an American Baptist."

While holding target practice, a Chinese artillery unit fired bullets into our area. Colonel Swanson asked its commanding officer to stop the firing before they killed someone. The officer replied, "If anyone gets killed, the shooter will be shot" . A Ghurka native visiting our hospital traded knifes for cigarettes. I wanted a foot long knife that Ghurkas used for clearing jungle vegetation and more dangerous acts. He held up six fingers, and I handed him six packs of cigarettes in exchange for the knife. When I bragged about my good deal, a room mate, said, "Hey, the guy only wanted six cigarettes not six packs". Years later, as I proudly showed Vyette my prize possession, she said, "Get rid of it. I do not want it around the children."

Naga Headhunters serving as guides believed they would have a good harvest by sacrificing human heads to their gods. A rice grain was placed on the road. If a stranger crossed the road, they felt their God wanted him sacrificed. Luckily they were on our side. A nurse checking on a Naga patient was surprised to find his three wives keeping him company in bed.

Some of our Jewish soldiers wanted to hold a traditional Passover Seder. We found a Chinese restaurant willing to provide facilities on the Ledo Road. This was not easy, since the Chinese cooks could not speak English. Armed with brushes, soap and water, we cleaned the place. The Jewish Welfare Board provided matzos and prayer books. The Catholic chaplain contributed sacramental wine. We helped prepare matzo ball soup, chicken and other holiday foods. Hospital sheets served as table clothes. Accompanied by an accordionist, our commanding officer, chaplain and guests joined in singing Passover songs. By the end of the evening, we all sang, "When Irish eyes are smiling."

The Ledo Road was narrow, with ankle-deep mud, treacherous turns and no shoulders. One rainy afternoon, I was traveling by Jeep to pick up the unit's payroll at Base Headquarters. My driver, stepped on the gas whenever we rounded a turn. He swerved, and the Jeep turned over on its side. We and the car were not scratched. GI's in a passing truck, put the jeep back in position. The driver nonchalantly continued to drive back to the hospital, stepping on the gas as we rounded the curves.

When the Post Exchange truck arrived, our men lined up to purchase rationed cigarettes, beer, chocolates and fruit juice. There was a drawing for scarce items. A lucky bald fellow could win a bottle of hair lotion. A cook might get a can of deviled meat. Only at a P.X. would a nonsmoker stand in a long line to buy cigarettes to trade for something he did not need.

When we arrived in India, we had an APO address, and the army censored our mail. Later, we were permitted to write "Somewhere in India." Toward the end of our stay, we could say "Ledo Road." Mail call was the most popular event of the day. My brother, Joe, an army technician/4, wrote regularly. I do not recall if he had a driver's license, but he drove heavy tank destroyers and amphibian tractors. A sharp shooter on many weapons, he served in Leyte, Philippines, New Caldonia and Japan. My brother, Dan, who worked in a defense plant, kept me in touch with the home front happenings.

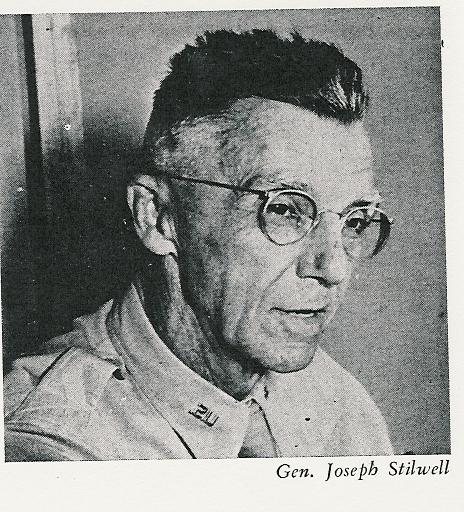

Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell, affectionately called Vinegar Joe, commanded the China Burma India Theater forces. Wearing a peaked hat, and field jacket, with no insignia, he fought, ate and slept with his men. The general, who was more than 60, told about the soldier who said to him, "You look too old for this sort of thing. Why don't you ask them to send you on home?" Because of conflicts between General Stilwell and General Chiang Kai Shek, President Roosevelt recalled Stilwell to the United States before the war ended.

Merrill's Marauders

I have always admired the Merrill's Marauders who made such extreme sacrifices and contributed so much to the war effort. Merrill's Marauders, a jungle trained group, with their horses and pack mules, trudged by our hospital in the Spring of 1944. These heroic men had fought in New Guinea, Guadalcanal and other Pacific Island battles. Commanded by Brigadier General Frank Merrill, they were on their way through dense jungles to open a route to China. They were heading toward Myitkyina, a strategic airfield and town. On the way, they had five major battles with the Japanese army. Wounded and sick Marauders were carried to evacuation points where small planes landed and took them to hospitals.

We set up a branch hospital in Margarita, India. Many soldiers required surgery or suffered from poor nourishment, malaria, dysentery, jungle rot, and mite typhus. Soon, the hospital cared for 1,500 seriously ill Marauders. Because of the troop shortage, superior officers ordered convalescent Marauders to return to the front lines. Our medical officers refused to release those men too weak to return. General Frank Merrill, who suffered two heart attacks in combat insisted on joining his troops.

The Marauders, Chinese troops and Kachin guerrillas defeated the Japanese and captured Myitkyina. Following this battle, the Marauders disbanded. The Mars Task Force, a brigade consisting of remaining Marauders, Texas National Guards and Chinese troops replaced them. Allied ground and air attacks drove the Japanese out of Burma.

The C.B.I. Theater was divided into a China Theater and Burma India Theater. The road now provided a supply route of 1,079 miles from Ledo to Kunming, China. The first convoy of trucks reached Kunming after traveling twenty days. Engineers, mainly African Americans, deserve much praise for their efforts despite deplorable weather and combat conditions. The combined Ledo and Burma Roads were renamed The Stilwell Road.

Vacation Time

After more than 18 months overseas, I was ready for a vacation. I flew to Calcutta and stayed at a Red Cross Rest Facility for a few days. When I was sightseeing, I saw how Calcutta's beautiful Temples were in contrast to its slums. I dined with army buddies at Firpos, Calcutta's most popular restaurant.

Leaving Calcutta, I boarded a train bound for Puri, Orissa, 300 miles south. This seaside town is the home of the Jagganath, a holy Hindu site. Pilgrims travel for miles in the hope of being cured of their illness. For a glorious week, I stayed at a Red Cross rest resort previously owned by an Indian Maharaja. I enjoyed good food, bathed in the warm sea water, fished, rode bicycles and went sightseeing. At the Monkey Temple, a religious shrine, huge, chained orangutans guarded its entrance. While I fed him peanuts, he grabbed my wrist and helped himself. His hands felt like a vise, and he was welcome to all of my peanuts. In the evenings, I played Bingo, shuffleboard, table tennis and swapped stories with friendly British soldiers at their club. Their rum tasted like paint remover.

My Puri vacation ended too soon, and I boarded a train to return to Calcutta. Soldiers drew lots for beds in the crowded train. I lost the toss and slept on the floor. In Calcutta, the Lenyados, who were prominent in the comunity, invited me to their elegant home for several sumptuous meals. Hannah, their teen-aged daughter, wanted to know all about the habits of American women. (As if I knew.) I later sent her American cosmetics purchased at the Post Exchange. The Lenyados took me to the Calcutta Race track where I shared a $2.00 ticket with another soldier. Moose came in first, and we won 220 rupees (about 70 dollars). My vacation over, I left Dum Dum by plane and return to my unit.

The War Ends

With the war in Europe ended, a soldier from the army's Special Services Division, showed us movies of American troops liberating Nazi death camps. These films depicted the inhuman atrocities committed by German soldiers. As we celebrated our victory, the horrible revelations shocked us.

On a sad note, Captain Jewel Roberts, who had completed his military service, died of mite typhus while flying home. Before he left, we held a farewell party in our basha. A pathologist, he was chief of our hospital's laboratory. He was married and never saw his child who was born after he went overseas. Our grieving personnel attended a memorial service for this popular officer.

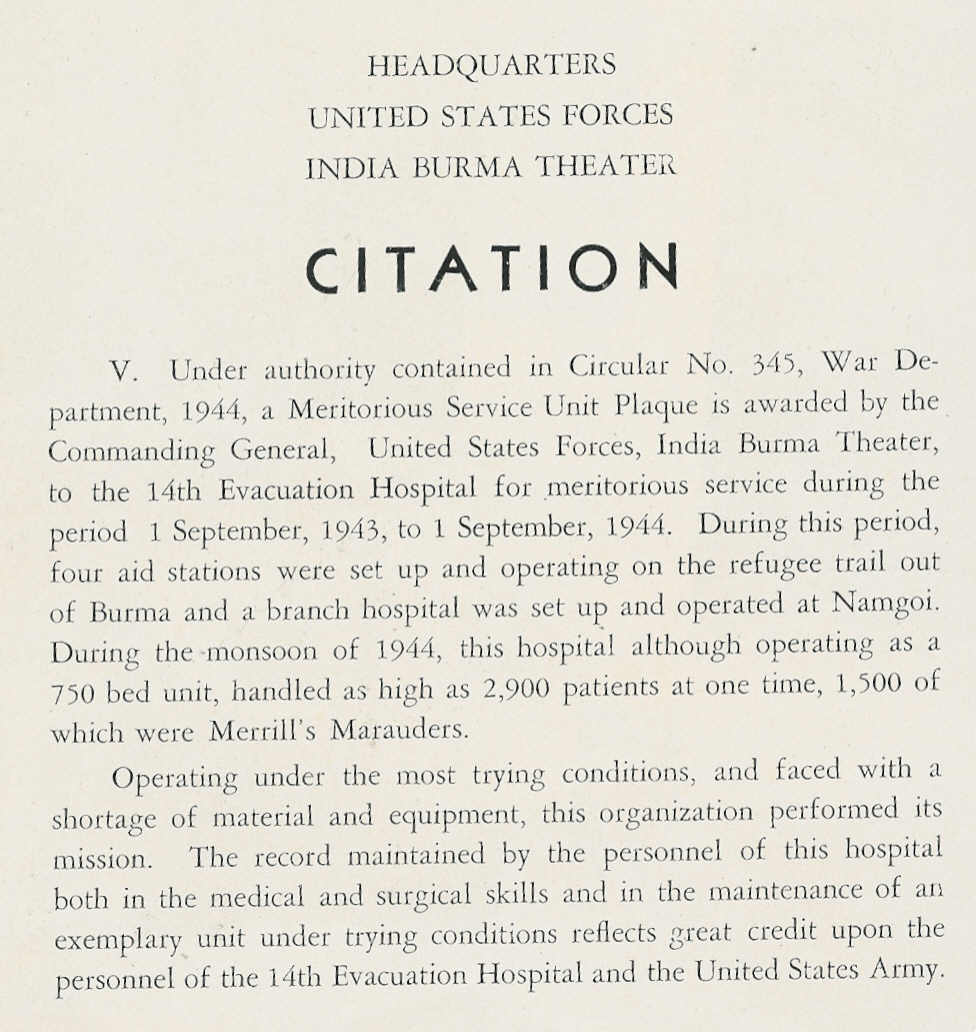

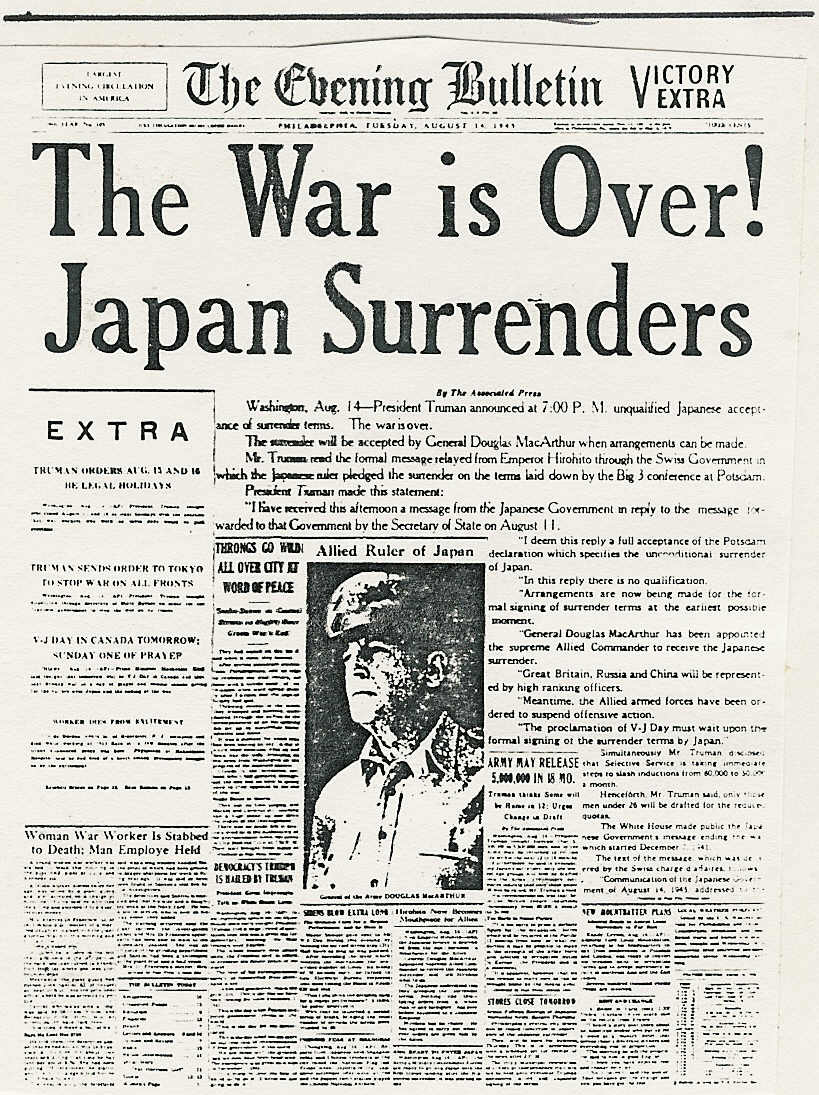

Following the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan surrendered to General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz aboard the Battleship Missouri, September 2, 1945. The war was over! After inspecting our facilities, records and personnel, the Inspector General gave our hospital a superior rating. A Meritorious Unit Service Citation from the Commander of the Burma India Theater reads in part: " The record established by the personnel of this hospital and in the maintenance of an exemplary unit reflects great credit upon the personnel of the 14th Evacuation Hospital and the United States Army." General Frank Merrill cited the hospital for its "excellent medical performance". (After the war, I spoke with the general who was in Philadelphia and was thrilled to exchange memories with this American hero.)

Finally, I became eligible for discharge under the army rotation plan. Saying good-bye to my longtime friends was difficult. I left India September 7, 1945 traveling in an army two engine cargo plane with no seats. We made stops at New Delhi, and Karachi. Suddenly, one of the plane's two propellers caught fire. We were forced to land at Lydda Airport in Tel Aviv. While mechanics repaired the plane, I visited the city and shopped for souvenirs. I purchased a beautiful painting of Jerusalem's Western Wall that hangs in our living room today. One frightened soldier did not show up, and our plane took off without him. We made other stops at Cairo, Tripoli, Casablanca, The Azores and Newfoundland.

Home at Last

After a seven-day flight, I Arrived at Washington Airport, September 14. I headed for a restaurant and ordered a glass of pineapple juice. The waitress scowled at me and said, "Don't you know there is a war going on?" After traveling by train to the Indian Town Gap Separation Center I received a two-week furlough. At last, I was finally able to spend time with my family and friends, sleep in my own bed and choose my food. Upon returning to the Gap, I was honorably discharged as a master sergeant October 8, 1945 and transferred to the inactive Organized Reserve Corps. Remaining members of the unit closed the hospital and left for home. The 14th Evacuation Hospital was deactivated December 4, 1945.

Since I was caught in the draft, much had changed. My mother and father had passed away. ( I was overseas and unable to attend my father's funeral.) Dan, my older brother, had married, and I now had a niece. Joe, my younger brother, was overseas with a tank destroyer outfit. Several close friends were killed in action. My civilian clothing was too tight.

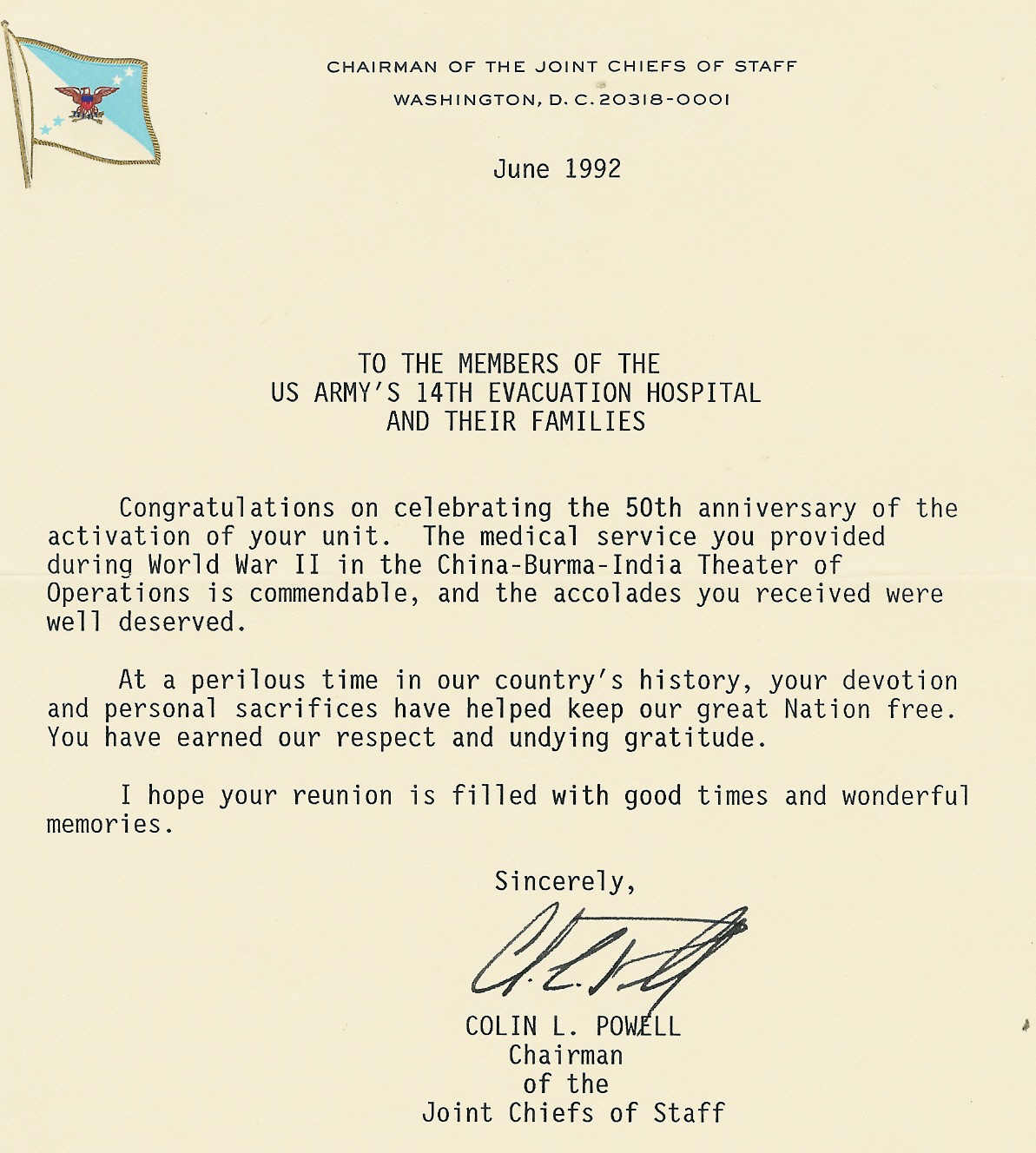

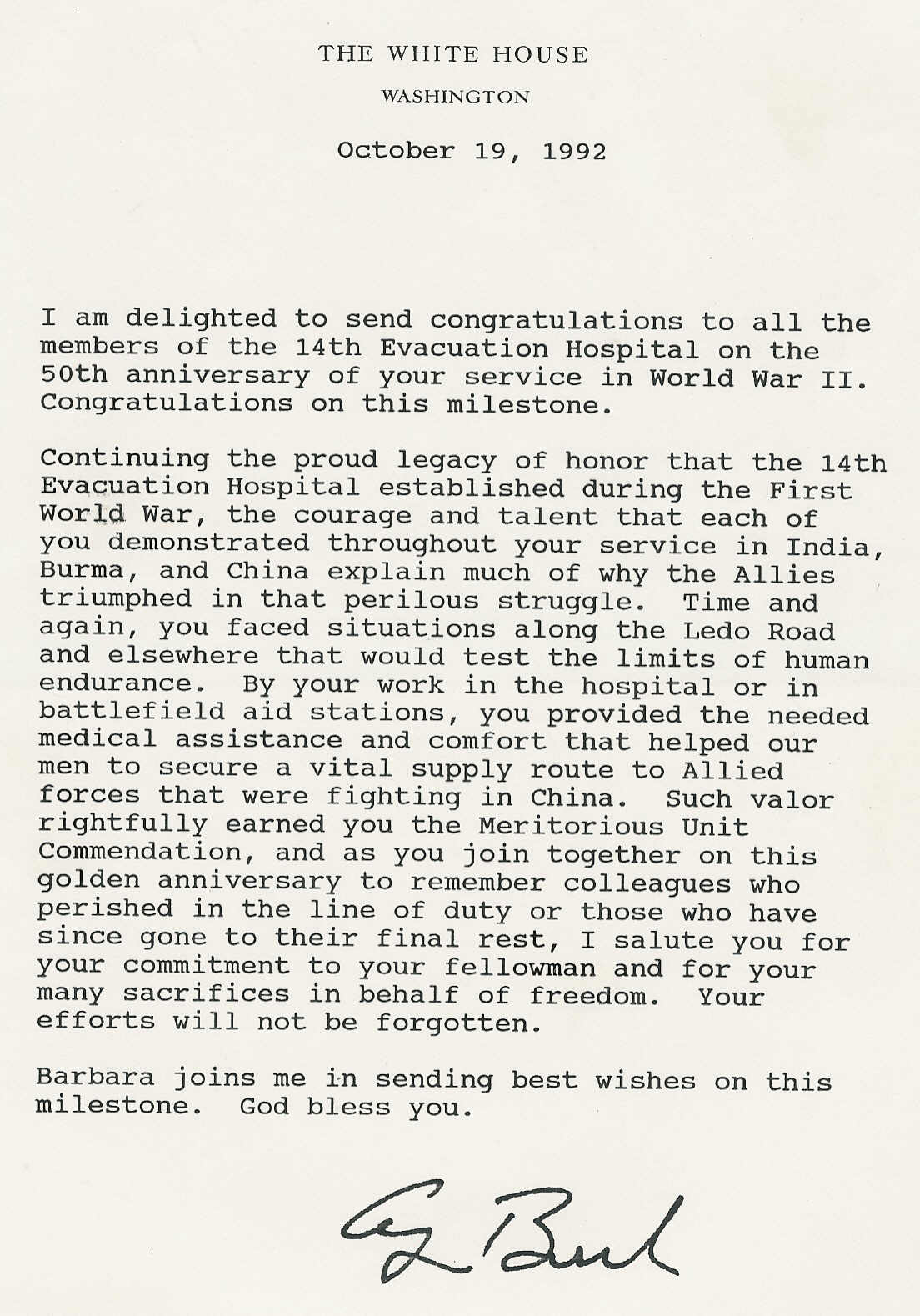

We originated the 14th Evacuation Hospital Reunion Group in 1975, and I served as its vice president. Our members hosted annual meetings. Vyette and I were hosts at Philadelphia's Marriott and later at Caesars Hotel in Atlantic City. The group celebrated the 50th anniversary of the activation of our hospital in Watertown, New York in 1992. Commendations came from President Bush, Secretary of the Army, Secretary of Veterans Affairs and the Army Surgeon General. Senator D'Mato introduced a resolution printed in the U.S. Congressional record lauding our accomplishments.

General Colin L. Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff wrote, "The medical service you provided during World War II is commendable. The accolades you received were well deserved. At a perilous time in our country's history, your personal sacrifices have helped keep our great nation free. You have earned our respect and undying gratitude. When traveling became difficult, the group disbanded in 2001. We donated our treasury to the World War II Memorial under construction in Washington, D.C.

As a public relations counselor in 1991, I accompanied Dr.Gerald Lemole, a cardiovascular surgeon, and his team to Beijing, China. He formed an alliance between the Medical Center of Delaware and the Fengtai Institute, a Chinese Hospital. Dr. Hong-XI-Su, who headed the hospital, served with a Chinese medical unit on the Ledo Road, a few miles from our hospital during World War II. We had a great time swapping war stories.

During the observance of the 50th Anniversary of World War II, The Department of Defense created a World War II Commemorative Committee to conduct activities honoring World War II vets. I organized and chaired the Philadelphia Hero Scholarship Fund Commemorative Committee and served on the Naval Aviation Supply Committee. At the Naval Supply office Commemorative Service, I said, "This is an exciting age with ingenious advances in technology, communications and science. We should devote the same insight and enterprise to techniques that promote peace. A lasting peace and strong democracy are the best legacies we can deliver to those who sacrificed their lives so that so that others can live in freedom."

I spoke at the World War II Lecture Institute in Abington, Pennsylvania Juy 15, 2003. This splendid organization conducts monthly lectures and draws big crowds. The lectures are taped for display at The Library of Congress. I now serve as a public relations officer and board member of the organization.

My military service had a major impact on my life. As a young man, I developed organizational skills and learned how to interact with people who had diverse backgrounds. I am happy to have played a part in our country's history.

This memorial to British soldiers killed in Eastern India also applies to America's fallen heroes: "When you go home, tell them of us and say, For your tomorrow, we gave our today."

Milton A. Eisenberg, and Vyette, his wife of 57 years, live in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania. Before his army service, he was an assistant superintendent with Yellow Cab Company of Philadelphia. In later years, he became president of the company. Upon his retirement, he formed Eisenberg Consulting Services, specializing in public relations for hospitals, law firms and nonprofit organizations. Active in community affairs, he helped originate the Philadelphia Hero Scholarship Fund and later served as its president. The fund provides four year college scholarships for the children of police officers and fire fighters killed in the line of duty. He also chaired the Philadelphia Police Athletic League, National Conference of Christians and Jews and serves on civic and charitable boards.

|